As the Baby Boom generation ages, and depending on whom you ask, estimates are that they will pass some $50–80 trillion to their heirs over the next several decades. This means that many Millennials may soon find themselves in the position of needing to make some important decisions as they settle the final affairs of their parents and perhaps other older family members. Many, in fact, may be designated as executors for their parents’ estates, which will place them squarely in a position of great responsibility.

But how much do most really understand about the basics of estate planning and inheritance law? In this article, we’ll provide a brief summary of some of the more common estate plans and offer an overview of the responsibilities of an executor.

Basic Estate Planning Structures

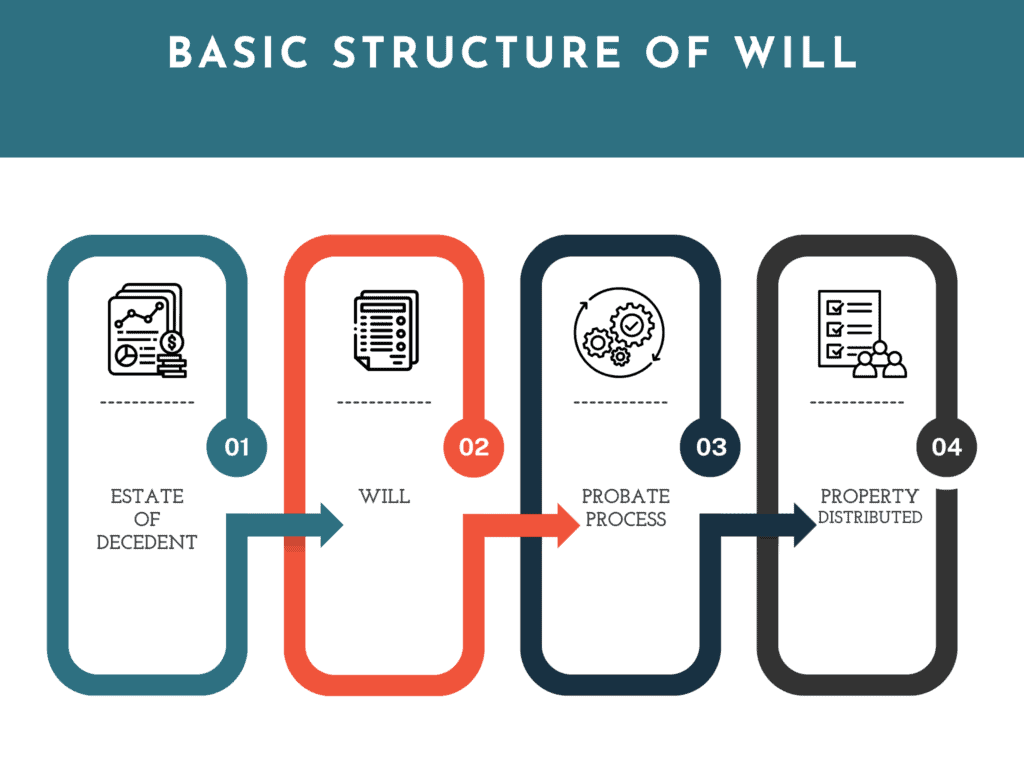

Perhaps the most common estate plan is a will. The person who provides the will is the grantor or testator, and the persons receiving the proceeds are the beneficiaries. When the testator dies, they may be identified as the decedent. The basic structure of a will looks something like this:

The will documents the decedent’s wishes for how the proceeds of the estate are to be distributed upon death. The probate process is administered by the courts of the state in which the will was filed, and the executor is responsible for seeing that the terms of the will are followed. In most simple wills for married couples, the spouses are the beneficiaries of each others’ estates (“reciprocal wills”), and children or other family members are the beneficiaries following the death of the surviving spouse. Of course, the testator may also designate other beneficiaries, such as other family members or charitable organizations.

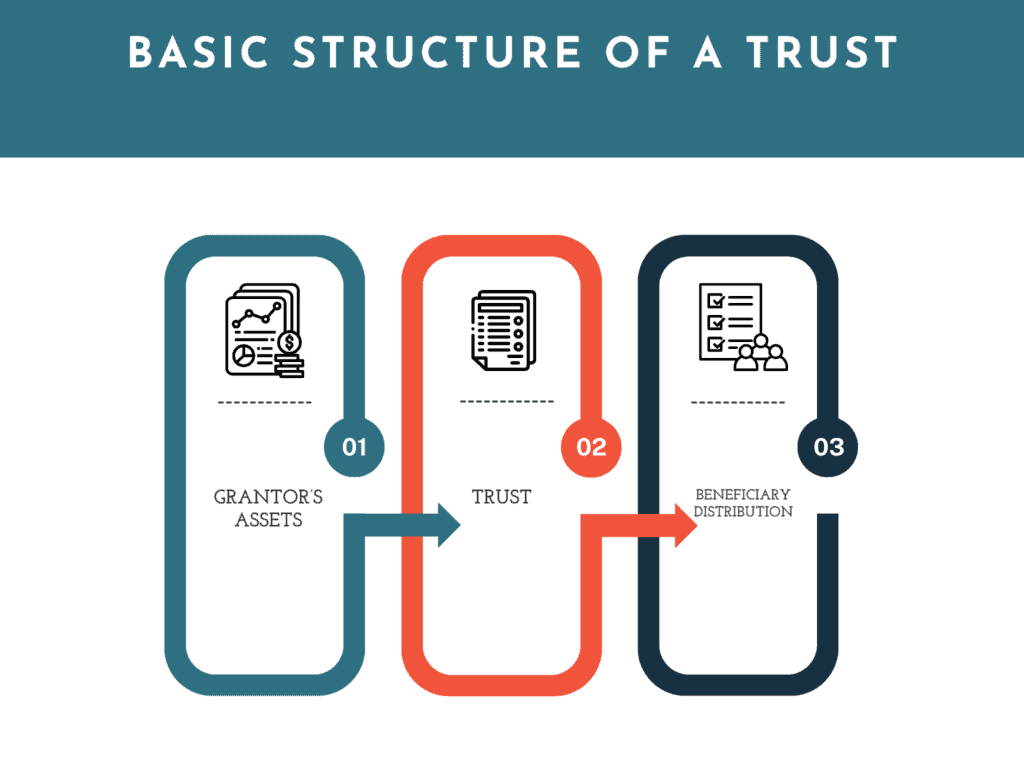

Some, rather than using a simple will, may wish to establish a trust to hold the assets of the estate. A trust is a legal instrument that is empowered to hold, manage, and distribute property according to the terms specified by the person creating the trust (the “grantor”). The principal advantage a trust has over a will is that the trust can survive the death of the grantor and thus does not typically require probation by the courts, as does a will. Those who wish to avoid the time and expense of probate—and especially those with more extensive or complicated estates—may opt to utilize trusts of various kinds for the disposition of their estates. Another advantage of trusts is that they can contain various conditions for the management and distribution of assets other than the death of the grantor. For example, someone who has a child with special needs might set up a trust to hold assets for the benefit of the child, and the trust would be responsible for administering and disbursing the assets as long as the child needed them. The basic structure of a trust is something like this:

The individual or entity responsible for seeing that the terms of the trust are carried out is the trustee. It’s also important to note that there are several different ways of structuring a trust, depending on the needs of the estate and the wishes of the grantor. There are even trusts that may disburse certain funds to the grantors during their lifetime, then continue distributions to beneficiaries following the death of the grantors. For estates considering the use of a trust, consulting with a qualified estate planning professional or attorney is essential to make sure the trust being considered is appropriate for the estate’s purposes.

What Does an Executor Do?

As mentioned earlier, the most common type of estate planning involves a will, which appoints an executor to oversee the probation of the will and the distribution of the estate’s assets. While this is not intended as an exhaustive discussion, let’s take a look at some of the basic duties and expectations of an executor.

- Obtain a copy of the will and file it with the local probate court;

- Notify banks, credit card companies, investment firms, and government agencies of the decedent’s death;

- Represent the estate in court as necessary;

- Procure and file with the court a proper inventory of the estate’s assets;

- Maintain the property until it can be distributed or sold;

- See that any final debts and taxes owed by the estate are paid;

- Distribute the estate’s assets to beneficiaries.

- Maintain accurate records of all assets and transactions.

As you can see, there’s a lot involved. A survey by EstateExec, an online tool for executors, found that the typical estate takes about 16 months to settle and requires 570 hours of effort. Estates worth $5 million or more typically take 42 months to settle and 1,167 hours to complete. Some of those hours will be hired out to professionals—attorneys, a CPA, or a wealth advisory firm—but the executor has to watch over and coordinate everyone’s efforts.

Further, disputes are not uncommon. You may find yourself in the role of referee when the heirs disagree about the way the assets were divided, and they may disagree with some of your judgment calls, such as whether to spend the estate’s money to fix up a house for sale.

For all these reasons, the role of executor for larger and more complicated estates is often assigned to a legal professional specializing in estate planning and management, or to an institutional manager such as a bank trust department. Most states’ laws allow for an executor to be compensated for time spent in managing the estate, but when the executor is a friend or family member, they often decline payment. However, that doesn’t mean the job won’t require time, effort, and emotional commitment.

As a fiduciary wealth manager, The Planning Center works with clients to help them make wise decisions about managing their assets, both now and in years to come. To learn more, visit our website to read our article, “Tips for Keeping Your Estate Plan “In Plan.”